Hidden populations and challenges measuring progress towards the SDGs? The case of signing Deaf women in Cape Town

In July this year, South Africa reported to the United Nations on the country’s progress to meet the Sustainable Development Goals. The SDGs are committed to “leave no one behind”. This principle includes disabled people, which is a welcome first: The SDGs are the first international call to action to include disabled people since the primary healthcare Alma Ata conference 50 years ago. Disabled people are neither mentioned in the Global Strategy for Health for All by the Year 2000, nor in the Millennium Development Goals.

The SDGs are, therefore, inclusivity in practice. But in practice it is challenging.

To monitor and measure progress, the SDGs require “high-quality, timely and reliable data that is also disaggregated by ‘disability’”. But, data and statistics compiled and analysed in a December 2018 report indicate that persons with disabilities are not yet sufficiently included in the implementation, monitoring and evaluation of the SDGs. Many national statistical systems across the globe face serious challenges in this regard. As a result, accurate and timely information about certain aspects of people’s lives are unknown, numerous groups and individuals remain “invisible”, and many development challenges remain poorly understood.

Recent work of the Health and Human Rights programme in the Public Health Medicine division of the School of Public Health and Family Medicine has been focusing on the maternal health of Deaf women of child-bearing age. “Deaf” capitalised refers to permanently sensorially and legally disabled women with congenital or early onset of audiological deafness and whose first language is South African Sign Language (SASL).

According to the United Nations Development Programme, the developing world accounts for 99% of all maternal deaths, and is where 80% of persons with disabilities reside. Yet, the developing world still has no credible quantitative data on pregnancy histories and outcomes of disabled women.

Our interest is to establish a monitoring and evaluation mechanism to track the implementation of policies and programmes on access to sexual and reproductive health for persons with disabilities. We want to improve research and data to monitor, evaluate and strengthen sexual and reproductive health and services for persons with disabilities.

Deaf (and other disabled) women, as a hidden and hard-to-reach population, pose challenges for monitoring and evaluation. They are not easy to access for research and health care. As a population, Deaf people do not have a defined geographical base and healthcare attendance is dispersed across a range of services and sites. It is near impossible to identify Deaf women through medical records as few developing countries, including South Africa, have electronic medical records implemented in public sector health facilities, and disability status of patients remains largely unrecorded. A challenge is the absence of a method that provides a representative or probability sample that allows extrapolation to the wider population.

Methods have been developed to address the challenges of sampling hidden populations – but these methods tend to be costly and time consuming. We are working to develop a protocol that is easy to implement, cost-effective, and rigorous, and that can be evaluated by comparing what Deaf women report about their pregnancy histories to data in the Provincial Health Data Centre (PHDC).

We began with an urban-based study in Cape Town, in 2016, with the support of Waru Gichane and Maraya Fontes, interns from the New York-based Mt. Sinai International Exchange Program for Minority Students. Forty-two signing Deaf women of child-bearing age were interviewed, using a structured questionnaire conducted in SASL. The study found that rates of successful pregnancies, miscarriages and terminated pregnancies in this population closely resembled rates among women in the general population of the Western Cape. Most Deaf women, however, reported experiencing communication issues due to limited interpretation services. When asked how to improve maternity services, the women resoundingly suggested increased access to interpretation services.

The reliability results showed that out of 19 questions, 14 demonstrated substantial to perfect agreement kappa scores (kappa between 0.61 and 1) and 5 had the lowest kappa agreement scores (kappa <0.61). With respect to percentage agreement, participants provided identical responses in 87% cases. Overall, women provided more reliable responses for pregnancy outcomes than for demographic information. Validity analysis showed that 29 out of 35 Deaf women provided survey responses that matched or nearly matched (83% agreement) the PHDC database for birth history and delivery location.

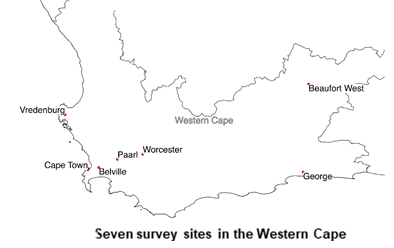

We are developing a protocol that is easy to implement, cost-effective and rigorous, and which will be piloted in a targeted multi-site, provincial-level study with non-governmental organisations providing points to access Deaf people (see map). By extending the work to rural areas, we seek to reduce the marginalisation of rural Deaf women.

If we are to make progress towards the SDGs, and particularly to leave no-one behind, we need research that can reach hard-to-reach populations such as Deaf women, wherever they are.

In memoriam: Dr Marion Heap, who passed away in August, was a longstanding member of the School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Health Sciences Faculty, and also worked and studied in other parts of UCT over a number of years. She was well known in the Faculty and across Cape Town for her research and advocacy for the right to health for individuals with disabilities, in particular regarding issues of language and the rights of the Deaf to SASL interpretation when accessing health care. With others in the School, she argued for greater attention to the deaf community in public health services, introduced innovations through different interventions in this area, and spearheaded sign language training in the Faculty.