Counting women’s work

The Counting Women’s Work is an international project which measures the gendered economy, including unpaid care work. The project provides data and analysis to help develop better policies on economic development, care for children and the elderly, investments in human capital, and gender equity in the workplace and the home. Valuing unpaid care work is important because care-giving sustains families and, ultimately, helps to preserve society. While it contributes considerably towards a country’s total welfare and economic output, the value of unpaid care has been difficult to determine because standard measures of economy only include care if it is paid for.

The CWW is a project within the National Transfer Accounts (NTA) project which stretches across 60 countries and uses standardised methodologies and tools to measure how people at each age produce, consume and share resources and save for the future. The CWW’s specific contribution to the NTA is to give insight on how males and females across all ages produce, consume, transfer and save, as well as to estimate the time and monetary value of unpaid care within households. Unpaid care includes housework such as cooking, cleaning, household management and maintenance, and direct care provided to children, elders, and the community. CWW results are also able to inform the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal indicators relating to gender.

South Africa’s women carry unpaid care burden

The South African component of the CWW research spans data analysis for 2000 and 2010, respectively. DPRU researcher and CWW South Africa project coordinator, Morné Oosthuizen, says the findings show that women still do the vast majority of unpaid care work: “By drawing on the Time Use Survey 2010 data from Statistics South Africa and NTA data for 2010, household production is valued at R749.9 billion in 2010. Almost three-quarters of this household production was contributed by females.”

Oosthuizen used a specialist replacement wage to calculate household production in monetary terms and found that such production was equivalent to 27.3% of GDP. “To put this into context, labour income is estimated at 51.1% of GDP. Females contribute 73.8% of the value of household production, while 57% of the total was accounted for by women and men aged 18 to 39 years.”

Source: Oosthuizen, M. (2018) Counting Women’s Work in South Africa. Incorporating Unpaid Work into

Estimates of the Economic Lifecycle in 2010. Cape Town: Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town. P. 12.

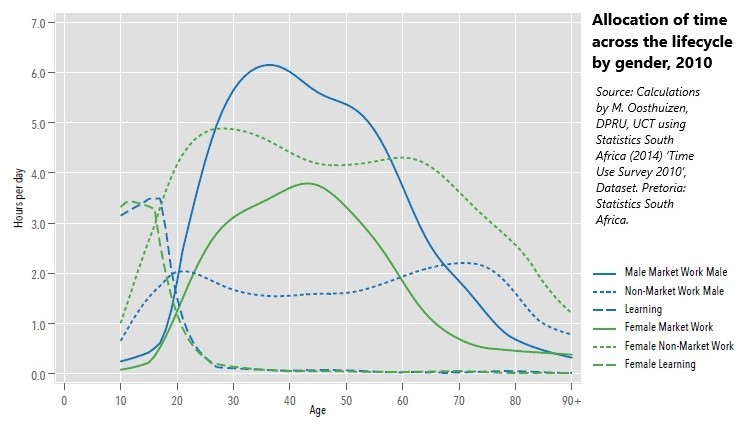

Data analysis shows that females’ time on housework rises rapidly during the teens and early twenties, remaining relatively stable from the late twenties to the early sixties after which it declines. Two peaks in females’ time-use on housework were found – around age 30 and then again around age 60. Men’s peak times on housework occur respectively sooner and later than for females.

Women’s time allocations for care is highest during their twenties and thirties. The data analysis shows that males, though, spend little time in care activities at any age: “Men’s peak time allocation to care is observed during their seventies. They account for less than one-fifth of all the time allocated to care, and just 11.2% of care for household members.”

In looking at consumption patterns from birth until old age, it was found that the per capita consumption of infants tripled when household production is included alongside estimates of market production and consumption, which shows that “the majority of the consumption by infants and young children is of non-market services, particularly care”.

Oosthuizen points out that these results reveal the substantial “hidden costs” of young children: “Infants and children are therefore the highest consumers of unpaid household production. This is an important result given its implications for policies related to encouraging women’s greater economic participation.”

Females outproduce males across the lifecycle

The time-use data show that, between the ages of 20 and 60 years, time allocated by both men and women to market work peaks, while time on housework does not vary as substantially by age. “But looking at the estimates by gender shows that males spend more than three-fifths of their total productive time in market work. They also spend more time in market work at virtually every age. Females, on the other hand, spend 71% of their productive time on household production at every age.”

Market work includes wage work in the formal or informal sectors, and work for household-owned businesses and farms; while household production includes unpaid care, housework and household management.

On the production side, the research shows that “males outproduced females at all ages in terms of labour income but, once non-market production is included, females outproduce males in per capita terms in all age groups up to ages 41 and after 72 years and older.” In other words, females for most of the lifecycle outproduce males in their per capita contribution to total production.

The reason why the burden of unpaid care work in South Africa is still largely carried by women is partly due to the high prevalence of labour migration which separates men from their families for long periods of time. Traditional ideas of "women's work" play a role as well. These come at a cost for girls seeking education and women looking for greater participation in paid labour.

Sharing unpaid work can boost economy growth

The South African analysis for the CWW project informed the CWW’s country report for South Africa, while the South Africa CWW team have shared the research with many policymakers in the country. The team also has been an important part of spreading the NTA/CWW approach to understanding age and gender in economies to other countries in Africa.

“One way that we have been using the results to gain some traction on the issue of unpaid work is to illustrate how reducing gender inequalities can boost the demographic dividend – the potential boost to living standards and economic growth resulting from falling fertility – and how sharing the burden of unpaid work more equitably underpins this.”

The research team makes several policy recommendations based on the findings. These include the need to acknowledge the importance of the every-day contributions of South Africa’s women to the nation’s well-being and total production, and to encourage a national conversation on norms around gender roles. They also recommend policies to support market-provided childcare for adult women and perhaps also for younger women whose final school years might be interrupted by family care responsibilities. Policies that encourage men to take more active roles in the household, especially childcare, and greater work flexibility for all parents, are also put forward.

Sustainable Development Goal 5.4 requires that countries “[r]ecognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate”.

The CWW is coordinated by the University of California, Berkeley; the Development Policy Research Unit at the University of Cape Town; and the East-West Center, Honolulu. The project has supported research in ten low- and middle-income countries around the world – Bangladesh, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, South Africa, India, and Vietnam.

Visit the CWW website for more details, research reports and other resources.

Article by Charmaine Smith, PII communication manager.