Grappling with Poverty and Inequality: Taking the Findings of the Mandela Initiative Forward

Why has it not been possible to give effect to the promised rights in the South African Constitution as quickly as people had hoped and expected? And what strategies can address the slow pace of transformation in South Africa? These were the key questions that steered the inquiries of the Mandela Initiative – a national multisectoral collaboration that emerged out of a UCT-hosted national conference, in 2012, on strategies to overcome poverty and inequality in South Africa.

The report on the MI process and findings was launched at a recent PII seminar. A key recommendation from the inquiry was that a focus on the poor only is inadequate because inequality is the most damaging legacy of apartheid, and requires urgent attention. The now-completed MI process could also serve as a springboard for the University of Cape Town to promote debate about a new vision for the country that can guide policy to reduce inequality and eliminate poverty.

For five years, between 2013 and 2018, researchers from six of the country’s universities, the Human Sciences Research Council, the Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (MISTRA) as well as government, civil society organisations and the private sector collaborated on what became known as the Mandela Initiative when the Nelson Mandela Foundation (NMF) joined as a strategic partner.

The MI’s goals were ambitious, Emeritus Prof. Francis Wilson, the MI’s national coordinator and founder of UCT’s Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, explained at the recent PII seminar where the MI report was launched: “Through its research, the MI aimed to influence public debate and policy about poverty and inequality; lay the foundations for developing an intersectional knowledge-based approach to eliminating poverty and structural inequalities; and – in this way – build a more equitable, just and sustainable social order.”

Steering such a complicated multidisciplinary and multisectoral project was a challenging although interesting task for the MI Secretariat that was based at UCT’s PII. It involved coordinating a high-profile national Think Tank of (past and present) government and business leaders, a number of the country’s leading researchers in poverty and inequality, and five university vice-chancellors, among others.

That was one ‘pillar’ of the MI’s work. The other included hosting 24 multisectoral action dialogues on topics pertinent to addressing poverty and inequality, and steering a research programme involving a number of of the South African Research Chairs Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and the National Research Foundation (NRF).

Input at these fora – and also 40 written contributions from participating researchers – culminated in a draft report on the MI's findings that were workshopped with key MI participants at a national conference in February this year, whereafter the report was finalised and launched recently.

Why the persistence of poverty and inequality?

Judy Favish, SALDRU associate and Poverty and Inequality Planning Group member, was instrumental in helping to draft and refine the report with the input of the MI Task Team, researchers and other collaborators. In presenting highlights from the MI report to the PII seminar, she explained that three layers to South Africa’s slow transformation in the interest of all were identified:

- micro-level traps (located at the education, health system, labour market and household levels);

- a legacy of structural inequality (pertaining to spatial inequality, land and housing, and wealth and other assets); and

- macro factors relating to the broader policy environment (such as social safety nets and social security, tax and expenditure policy, industrial policy and capital markets, the financial market, and macroeconomic considerations).

“The MI processes have surfaced flawed policies that perpetuate structural inequalities”, Judy told the seminar. These include the location and nature of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) housing projects, the language policy on the medium of instruction of the education system, and the dominant focus on the large-scale agriculture sector, for example.

“The inquiry also foregrounded policy gaps such as the absence of a youth support package, a guaranteed employment scheme, support to township economies, and dealing with the vast pay differentials in the country, to mention just a few”, Judy explained.

At the same time, some policies in key areas entrench “working in silos” or sit uncomfortably across the three levels of government, such as the locus of authority for decisions about health and transport services. These create barriers to transformation, which are compounded by poor capacity to, for example, realise land reform and implement the national policy on early childhood development (ECD).

Where to start?

With a magnitude of factors to address in order to shift poverty and inequality, the MI report proposes a useful framework for prioritisation. It outlines the importance of:

- implementing strategies that lay the foundation for the successful implementation of other strategies through, for example, igniting growth by investing in the urban landscape and ensuring that every child can read for meaning by grade 3;

- implementing initiatives specifically designed to break the cycle of intergenerational poverty, such as the integrated ECD framework;

- addressing other major drivers of the persistence of inequalities such as land and agrarian reform; and

- tackling inequality at the high end at the same time.

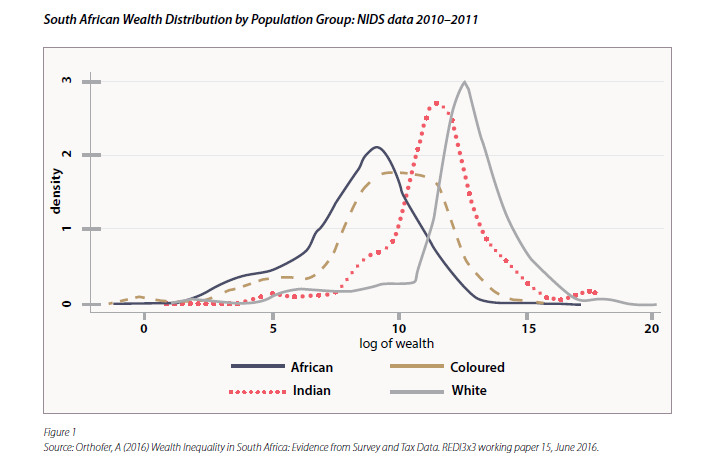

“Research by Anna Orthofer has showed that the wealthiest 10% of the population own at least 90 to 95% of wealth”, Judy told the seminar, “whereas 50 to 60% are in the highest income group. Thus, while the middle class is growing in income, it is not growing in wealth and is vulnerable thus to slipping back into poverty”.

The need for more concerted attention to engaging with wealth and privilege was one aspect of transformation that emerged out of the research and discussions at the February conference. The MI report points out that “[w]hite South Africans have not demonstrated a willingness to give up their privileges and there hasn’t been the requisite political will to tackle this challenge.”

The need to build a strong, vibrant civil society and a more capable and responsive state, and to do things differently and with ‘outside-of-the-box” thinking, are also highlighted.

Doing different things and doing things differently

The report encourages government to review levels of devolution (where more central steering or more authority at local level might be required) and to strengthen accountability at all levels. It also urges greater collaboration between different social partners. Of equal importance is to unlock and assist spontaneous social energies and use creative ways of soliciting ideas from local communities.

“The report highlights that we need to recognise and build on the agency of ordinary people. We need to be open to the construction of new kinds of typologies; we need a new mindset by moving away from compliance thinking to problem solving”, Judy explained. “Applying such a way of thinking will enhance the package of intersectoral policies in line with a clear vision that is proposed in the report.”

Judy added that the impact of such policies can be strengthened by incorporating lessons from evaluations and from good practice in interventions by the civil society, government and the private sectors.

Building on what works

One of the objectives of the MI was to surface examples of innovative practices that are tackling poverty and inequality across the country, and the report (and website) contain a seedbed of inspiring and promising cases of different sectors (and often in multisectoral partnerships).

Judy highlighted this potential legacy of the MI in her presentation: “It has resulted in relationships and connections with different networks and organisations that were nurtured over almost six years, and the website contains a useful list of organisations working in different areas across the country. We’d like to think that the seeds of transdisciplinary collaboration and networking that were planted by the MI process can create further potential for social partners to be involved in and advise on intersectoral policy implementation or required policy changes.”

This point was underlined by a seminar participant, Laura Berg from PovertyStoplightSA, who noted that there are 155 000 non-governmental organisations in the country: “We need to assess who are doing well in their fields, and those good practices should inform policies in a bottom-up approach”, she said.

Contributing to continued public debate

“A number of speakers at the February conference asserted that historical patterns of capital accumulation need to be disrupted. This means we need to put the struggle against poverty and inequality on a renewed and more radical footing”, Judy said. “And this includes the responsibility of UCT to facilitate public debates on inequality and poverty policy to help inform better strategies for transformation.”

Judy pointed out that there are different ways in which the University potentially could build on the outcome of the MI process. These include creating opportunities to reflect on policy-making processes, contributing to knowledge generation about approaches to development, hosting public seminars on a new vision for the country, and building the capacity of a new generation of researchers and academics to engage proactively with poverty and inequality problems and potential solutions.

With the work of the MI having drawn to a close, the NMF will be taking forward national conversations on two key areas identified as critical through the MI process: early childhood development, and land reform. Other ways of building on the work of the MI currently being explored by a broad network of partners.

Article by Charmaine Smith, PII communication manager, November 2018.